For people around the world planning or building wireless networks, the cost and accessibility of the equipment can often be a challenge. There are usually a few models of wireless routers, but they are generally for home or office use, and not intended to be mounted outdoors. In addition, most router antennas are designed to connect with nearby devices, within 100 meters or less.

With this limitation in mind, many community wireless networks decide to build custom Wi-Fi antennas to extend the range and capabilities of the wireless routers in their networks. Generally, this means that wireless routers used in community networks must have external antennas. If you have a router at home that is just shaped like a rectangle or box, chances are the antennas are inside the unit. Many modern routers have external antennas—small plastic cylinders (about as big as a pen or pencil)—extending out from the back or sides of the box. These can often be removed and replaced with custom antennas.

I’m always impressed when I see home-made antennas, and extra impressed when I see antennas being used in a way I just hadn’t thought of before. When I encountered documentation on the AlterMundi website about their custom antennas and how they are used in community networks in Argentina, I was intrigued.

AlterMundi is a community organization in Argentina (with partners around the world) that builds community wireless networks. I first met a few of their organizers at the 2013 International Summit for Community Wireless Networks (IS4CWN) in Berlin. I saw their presentation on how they built their custom antennas, but until I read the website documentation I didn’t realize how they were using them.

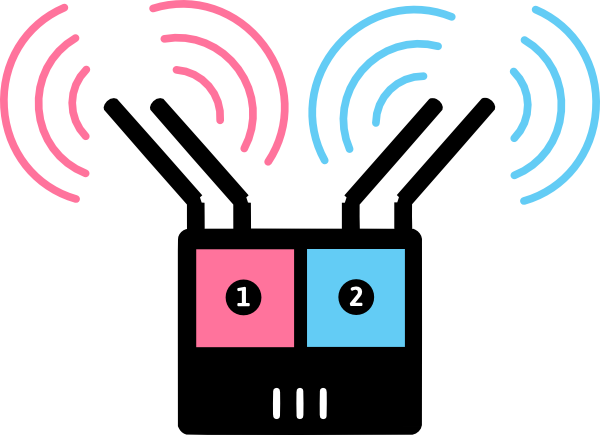

AlterMundi’s usage is interesting because they use the two MIMO (multiple-input multiple-output) chains in low-cost consumer routers to perform separate functions. A quick Wi-Fi MIMO primer: most consumer routers that have high throughput (N300, N450, N900, etc.) use multiple antennas to connect to devices with multiple “streams” of data. It is hard to visualize, but imagine instead of trying to make one pipe bigger, you can use multiple pipes at the same time. You could move more water through those pipes, right? Take a look at the example below.

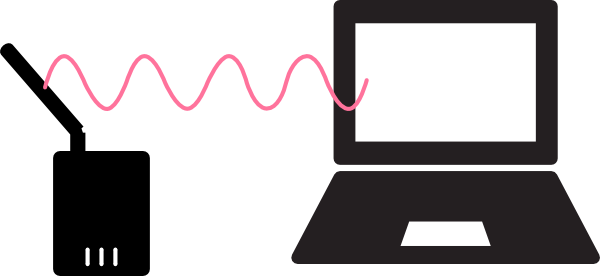

Wi-Fi without MIMO, standard throughput:

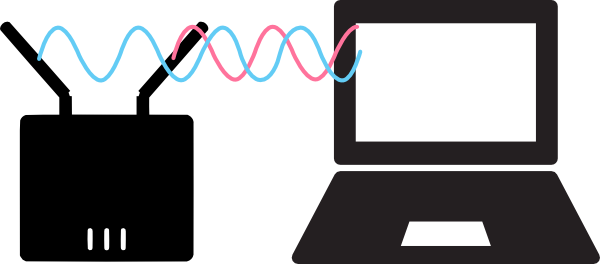

Dual-stream MIMO Wi-Fi, about double the throughput over standard:

While you may have more pipes, these are still connected to a single radio in the router (and in your laptop or phone). The “radio” is the chip inside of the router that sends and receives the signals.

For instance, below is an example of a Wi-Fi device with a single radio. It may be able to do multiple things at once, such as provide an Access Point for users to connect to, and a mesh link to connect to other nodes. However, it is restricted to use a single channel, for example Wi-Fi channel 11 on the 2.4GHz band. All of the communications on this node would use this single channel, and compete for connection time.

If you had a router with multiple radios inside, you could split up the functions, or make multiple connections on different channels. Below is an example of this type of router. You could have the Wi-Fi Access Point for users on radio 1, and the mesh link connections on radio 2. This allows for many more connections and lowers the amount of competition for time on the wireless channel, since the two radios can use different channels (Channel 1 and Channel 11 on the 2.4GHz band). This has the effect of increasing performance and throughput, but makes the routers more expensive and complicated.

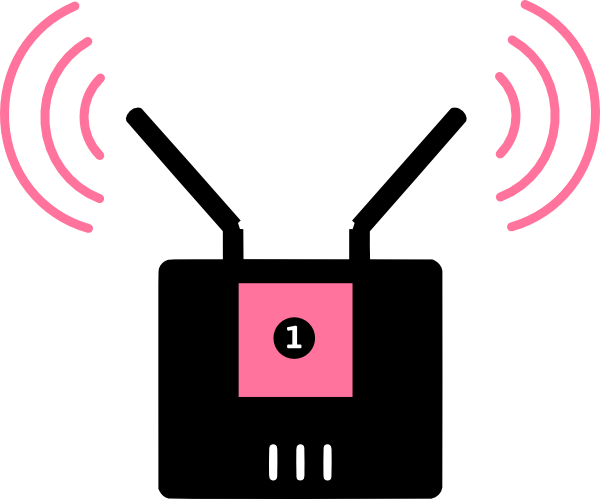

Both of the examples above use MIMO technology. Each radio has two antennas connected to it, which can double the throughput to user devices. If we didn’t care about throughput, we could do many more interesting things. AlterMundi uses three different antenna configurations for their mesh nodes:

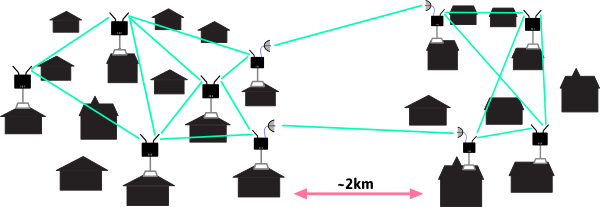

- Two omnidirectional antennas. These provide signal all around the mesh node, identical to how a home or office router would work. If the node is mounted outside, it can connect over longer distances, but usually only up to 100 meters or so.

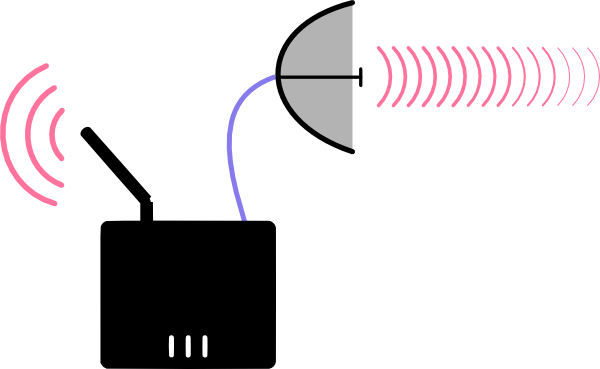

- Two long-distance dish antennas. These provide only long distance links for connecting distant points in the network, not for providing coverage around the mesh router. These can connect with other nodes up to several kilometers away.

- One omnidirectional antenna, and one long-distance dish antenna. The omnidirectional antenna creates an area around the router for users or other mesh nodes to connect to, but only over a short distance. The directional dish antenna creates a long-distance connection, but may require similar dish antennas at the other end to create a solid connection. This can bridge the gap between nodes that are far away and a cluster of nodes that are nearby.

For more details on how these nodes are built using off-the-shelf wireless routers and homemade dishes, see the AlterMundi documentation (in Spanish).

These designs are interesting because they make bridging the gap between long-distance links and local mesh networks easier, and much less expensive. Normally, a separate dish and Wi-Fi router are required to provide the long-distance connection at each end of the link. This would connect to another router with omnidirectional antennas, which would provide connections to users, other mesh nodes, or both.

For example - consider the scenario below. Two clusters of homes are separated by several kilometers. Normally, Wi-Fi signals from rooftop routers will not reach this far. With a few routers modified to use directional dish antennas, these two network clusters can be joined into a single network.

This approach isn’t without its drawbacks, though. As I mentioned earlier, these designs separate the two MIMO chains, and use them for different things. This reduces the available throughput for the Wi-Fi device by half. Instead of a maximum of 130Mbps, the maximum throughput would be 65Mbps (approximately). This is because the router can’t utilize multiple connections to a single device, as it is limited to a single stream to each antenna, which are connecting to very separate and distant devices.

Despite this drawback, I think the advantages make it very worthwhile in many cases. And as AlterMundi has shown, it does work quite well. If you know of any other networks trying things like this, or building do-it-yourself antennas, we would love to hear more about it. Get in touch on the Commotion Discuss or Developer lists and let us know about your experiments!

Deep tech note:

I simplified some of the technical points in the article above. Specifically, many routers today are dual band, which means they use both 2.4GHz channels and 5GHz channels simultaneously. This provides two “networks” on a single router, though they connect you to the same resources, typically. Most user devices, such as laptops and phones, only support the 2.4GHz band, but many modern devices now support both.

Technically, each of these bands requires a separate radio - one operating on 2.4GHz, and one operating on 5GHz. When I am discussing multiple radios in the article above, I’m just referencing a single band at a time. The “dual radio” devices I am referring to are two radios on the same band, which is why I mention the two separate channels on the 2.4GHz band.

The routers AlterMundi uses are TP-Link WDR3500, which are dual band, and therefore dual radio. They still only support a single channel on each band. For a router to support multiple channels on a single band, it would need to be multi-radio and multi-band. This would get expensive fast, because if you wanted to support two channels on two bands, that would take four radios. Three channels on two bands? Six radios.

Also, to keep costs down, consumer routers such as the previously mentioned TP-Link put the signals for each band on a single antenna. Since they are on separate frequencies, the 2.4GHz signal and 5GHz signal don’t interfere. Each MIMO stream gets it’s own antenna, so this antenna sharing happens twice. So when AlterMundi makes their custom antennas, those have to support both 2.4GHz and 5GHz for the long distance dishes. Which is what makes it so cool!